Cool Mommy: How Margaret Cho taught me to compartmentalize.

When I was introduced to Margaret Cho in the early 2000s it was as though I'd been handed something illicit, like it was a nod of acknowledgment that I'd been allowed into a community I didn't know for sure existed. Not in real life anyway. This was back in the days of Limewire and Ares Galaxy and 40 minute download times for a single song on a dial up internet connection. (If you're reading this, and you're from a music company, I'm simply referencing the era and not at all admitting that I illegally downloaded music or gay comedy albums. In an unrelated note: I know all the words to Hakuna Matata in French.)

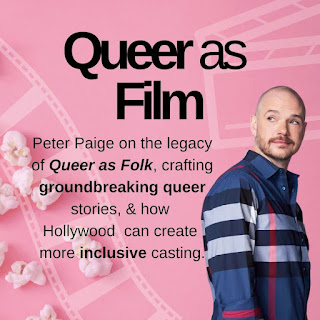

Like a lot of my cultural introductions from that time, Cho's comedy came to me by way of a recommendation and a file transfer from someone I've never met in real life. A fellow internet gay whose name and face I've since forgotten but who was navigating life in that weird space where Will & Grace was the number one comedy on television while Matthew Shepard was a name everyone knew. Network television saw success in Queer Eye for the Straight Guy while cable had the American adaptation of Queer as Folk. Literally any representation at the time felt like an actual miracle, but it came with understood rules. We could be gay, but we couldn't have a penis.

Oftentimes, existing in this space meant being okay with being the butt of the joke. When we were on television or film at all, we were either the victim of a hate crime, an AIDS patient, or our ostentatious homosexuality was making audiences laugh comfortably from their position of polite homophobia. This same laughing audience included my parents, my mother especially, who had gay friends in the orchestra and local theatre and a longtime relationship with her hairdresser whom she would have absolutely told you she loved.

I don't remember that internet guy's name, but I do remember that he sent me a clip from a Margaret Cho stand-up called "Are you gay?". It was the one where Cho's mother leaves her a voicemail asking her if she's gay after she worked a lesbian cruise. "Why you no tell mommy?" Cho cries in an affected mimic of her mother. "You can tell mommy. You have a cool mommy." The entire clip was somewhere around 4 minutes, and it made me laugh in that rare way where you actually think you're going to hurt yourself if you laugh any harder. Tears. Lots and lots of tears were shed. I laughed for problematic reasons I understood - accents are funny and because Cho is doing the accent I'm in on the joke while ignoring my own internalized racism - and reasons I didn't understand at the time - might I also be hoping my mother would ask me if I'm gay and tell me she's cool?

It was around this time that I'd become comfortable in what my relationship with my parents was going to be, the kind of relationship you see people grow into. Sure, I'd have to overlook the light bout of conversion therapy or the questions about whether or not I should be a mentor to young children because if I'm "confused" about my sexuality maybe I'm also a pedophile, but those were little things, right? With enough time and distance we'd do what we did with every other dirty secret in the family: we'd simply never talk about it. I thought I would move away and become an intellectual who wore a lot of sweaters and had a "roommate" and showed up with bells on to every family function. Beloved by my parents from a distance. I thought all of these things were aspirational qualities. The best I could hope for.

In that comfort, we shared a love of comedy. My parents loved comedians. They loved listening to comedy CDs in the car. There was the CD I got at church camp where my mother was scandalized because he said "What the hell?" at one point. There was, of course, Tim Allen and the rest of the network comedy lineup. As I got older and began working at a big blue box electronics store, I started discovering my own taste in comedy. Small names nobody had ever heard of doing edgy comedy like Ellen DeGeneres. (This is a joke.) I owned DeGeneres' comedy DVD. My parents and I watched it together. My dad to this day still quotes one of Ellen's jokes about there being too much pickle juice in pickle jars.

Edgy stuff.

They laughed at all of it, even the jokes about being gay. In retrospect I think I took that early laughter as a sign that maybe, just maybe, somewhere deep down, they were people who might one day be accepting of gay people. Like my mother's hairdresser. Like her orchestra colleagues. I took it all as patchwork promises of unspoken evolution on the matter. Now I understand that there was what they tolerated in other people and what was expected of their son. Homosexuality is something that happened to other people's families.

So, when I was a baby gay on the Internet getting by on dial up and a prayer and a mysterious older gay who seemed so mature, so worldly, sent me a hilarious comedy sketch, I of course thought I should have my mom listen to it. I remember the scene vividly.

My brother was there. My mother was there. We were using this massive Dell computer with the tower and the separate wired speakers and the mouse that would stop working if you thought about the color yellow or it was Thursday. We all laughed. A lot. We played it multiple times. We all took turns doing the accent and repeating the lines to one another. (Yes, that's incredibly awful. I was 17 and had no idea.) Then my mother, in the middle of our good time, says:

"I hope y'all know you don't have a cool mommy."

A part of me I hadn't named yet died right then. The cut was quick and clean. She was affirming that were either of us to ever come out, she would not be cool with it. My brother continued to laugh, utterly unfazed by what she had just said. I don't recall actually responding, because what do you say when you're not out and it's something like 2002-2003 and playing a pirated comedy sketch by a queer comedian was an unconscious testing of waters only to find out that the waters are deep and toxic? I know I stopped laughing and pretended I was very busy clicking something on the computer for a brief moment, then I continued in with the laughter.

My family continued to listen to Ellen DeGeneres comedy albums. We shared a love of Ron White and caught every episode of Whose Line is it Anyway?. When they later came to visit me in Chicago, we made it a point to go see a show at Second City. But, I never again played Margaret Cho around my parents. In fact, that was around the time I began screening content that I enjoyed before sharing it with them. It was around the time when I had to begin asking myself - mostly unconsciously - whether this funny thing I wanted to share would be ruined just a little bit if I shared it with them. Would there be a possibility of rejection and uncomfortable conversation? Margaret Cho's "Are you gay?" bit was a sign at a crossroads that I would come back to hundreds and hundreds of times in the subsequent decades.

It is this felicific calculus I have to perform that has created infinitely compartmentalized versions of myself. My parents know a version of me, but they do not know me.

I thought of this moment again a few years ago when my mother told me that one of her students had come out to her. She was frankly pretty devastated, because she didn't know what to do with this information. Why would he do this to me? she asked. What does he expect me to do with that? She told me that he'd looked at her social media and seen pictures of the two of us together. Smiling. Happy. All while I was very clearly gay. He asked if she might help him talk to his parents, because they were incredibly conservative and not cool. His thinking was that if she could accept me, she could also be a safe space for him, too. Except, she told him that I make her comfortable by not "throwing my lifestyle in her face". She told him not to expect acceptance and that if he was going to choose to tell them, he needed to be prepared to face those consequences on his own.

Another little part of me I didn't have a name for died then, too. By that time I'd been with my husband for over ten years. By then we'd shared integrated family gatherings. By then there had been a lot of opportunity for growth and change and evolution. But she was still quite comfortable in affirming that she would never be the cool mommy.

Comments

Post a Comment